Venomous and Non-venomous Snakes

Objectives

- Describe the key characteristics used to identify venomous and non-venomous snakes.

- Explain key elements about the biology of snakes that are important for their management.

- Communicate management options to clients.

- Describe the steps involved in properly treating snake bites.

Species Overview

Conflicts

Non-venomous snakes are usually harmless and cause no damage, yet many people are afraid of any snake. Occasionally, venomous snakes bite pets or livestock, causing physical damage and on rare occasions, loss of life. A person may be bitten by a venomous snake, but this is uncommon in the northeastern US. A bite from a venomous snake requires immediate medical attention.

Legal Status

Snakes are considered nongame wildlife and are protected by law in most states, unless they are about to cause damage to people or property. Never indiscriminately kill snakes. Some species are listed as endangered or state-threatened on federal and state endangered species lists. For example, the Eastern Massasauga rattlesnake (Sistrurus catenatus) is federally endangered in New York State.

Identification

About 150 species of snakes occur in North America, of which over 90% are non-venomous (Figure 1). All native snakes are beneficial to the environment, and are protected wildlife in many states. Timber rattlesnakes (Crotalus horridus) and northern copperheads (Agkistrodon contortrix) are venomous snakes native to some parts of the northeastern US. Consult a reptile field guide for detailed descriptions and range maps for different snake species.

Physical Description

Snakes are specialized animals with elongated bodies and no legs. They have no ears or eyelids, but transparent scales cover the eyes. A snake has a long, forked tongue, which aids the sense of smell. The tongue picks up particles from odors and inserts them into a 2-holed organ (the Jacobson’s Organ), in the roof of the mouth.

The 2 halves of the lower jaw are not fused, but are connected by a ligament. This allows snakes to swallow food much larger than their head size. Snakes are ectothermic (cold-blooded) and may eat only one meal in several weeks. Snakes may hibernate during cold weather, or aestivate during hot summer months. Snakes eat little or no food during times of decreased activity.

Color usually is not a main characteristic used to identify snakes. Coloration can vary greatly by area, genetic variation, and age of the snake. Features described below are used for identifying snakes.

- The keel is a ridge that runs along the middle of each scale in some snakes. Like the keel of a boat, the ridge may be pronounced, less pronounced, or absent. Rub a finger across the width of the skin of the snake skin to feel for the presence of a keel.

- Inspect the vent. Check if the scale that covers the vent is divided or single.

- Unlike color, patterns can be helpful for identifying snakes, although in some species, the pattern of juveniles differs considerably from adults. Identify whether the snake has stripes, blotches, or solid coloration.

- The distance from the snout to vent may be helpful but can be misleading in small snakes.

- The number of scales across the width of the snake may help identify the snake.

- Check if the head scales are large or small.

Pit Vipers versus Non-venomous Snakes

Several characteristics can be used to distinguish between pit vipers (venomous) and non-venomous snakes. All pit vipers have a deep pit on each side of the head, midway between the eye and nostril. Non-venomous snakes do not have pits.

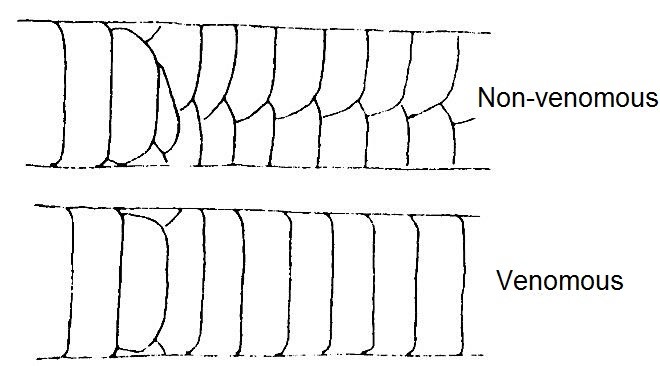

On the underside of the tail of pit vipers, scales typically (but not always) go all the way across in one row (Figure 2). On the underside of the tail of most non-venomous snakes, scales are in 2 rows from the vent to the tip of the tail. The shed skin of a snake shows the same characteristics. Because exceptions to the rule exist, do not use this technique to conclusively differentiate between venomous and non-venomous snakes.

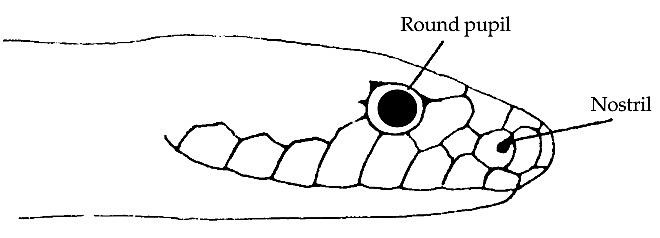

The pupil of a non-venomous snake is perfectly round (Figure 3). The pupil of a pit viper is vertically egg-shaped. In very bright light, the pupil may be a vertical line due to extreme contraction to shut out light.

Species Range

Consult snake field guides for information on the range of a specific species. State-specific guides to snakes also can be very helpful.

Health and Safety Concerns

Snakes that are native to North America do not hunt or attack people, although a provoked or harassed snake will defend itself. When people are bitten, it usually is due to the snake reacting defensively after being handled, threatened, or approached.

Never put your hands or feet into holes or other areas that you have not visually inspected. Wear leather gloves and use a snake tong or hook when capturing and handling snakes. When walking or inspecting areas where an encounter with a venomous snake is likely, wear protective leggings and always step on logs, as opposed to stepping over them without looking.

Exotic snakes present special safety issues. Exotic snakes are non-native species that once were pets, but were released into the wild. Some exotics are extremely dangerous due to their large size and toxic venom. While few complaints regarding dangerous snakes have occurred in the northeast, the risk is increasing as they become more popular in the pet trade.

Snakes have few diseases that are transmissible to humans. Salmonella is rare in wild snakes versus snakes from the pet trade. The exception is water snakes that may inhabit waters with abundant waterfowl. Some snakes carry ectoparasites but most are harmless to humans. Maintain standard sanitation procedures to protect yourself from snake-borne diseases.

A bite from a non-venomous snake will not harm the long-term health of the victim. Some individuals have been bitten several thousand times by handling non-venomous snakes, and suffered no adverse reaction. They only required basic first aid for any of the bites.

Non-venomous snakes cause harm by frightening people who are unfamiliar with them, and possible infection from a bite, just as with any break in the skin. A bite from a non-venomous snake should be treated as any other minor flesh wound. Clean the area and treat it with an antiseptic.

A bite from a venomous snake usually results in an almost immediate bodily reaction. Swelling, tissue turning a dark blue-black, a tingling sensation, and nausea are common reactions to snake venom. If no signs are observed or felt, the bite likely was from a non-venomous snake, or the bite did not contain venom (a dry bite). Over ½ of rattlesnake bites lack venom. Snakes dispense venom to capture and digest prey, and have little interest in people. Most snake bites occur in the suburbs. The following statistics offer a breakdown of snake bite occurrences in the US:

- reported bites in US is ~7,000 per year;

- 65% are from rattlesnakes;

- 55% to 60% resulted in no venom injected, and

- 50% of the people were handling snakes.

The probability of a bite from a snake being fatal in US is 0.002%. Typical victims are white males between the ages of 18 to 40 who have been handling a snake. In about a ¼ of these cases, alcohol was involved.

First Aid for a Venomous Snake Bite

First, move away from the snake to avoid any further bites, and keep others away from the snake. Try not to panic; stay as calm as you can. Panic will increase blood flow and the speed of venom travel through the bloodstream. Do not drink alcohol after being bitten. Alcohol dilates veins and will aid in the spread of the venom.

Seek medical care immediately. Call 911 and transport the victim to the closest hospital. If you are skilled at handling snakes, and the proper equipment is available (snake hook or tongs and a sealable container), capture the snake and bring it in for identification. A photograph of the snake can suffice, but stay at least 2 snake lengths away.

Remove constrictive clothing and jewelry. Swelling will prevent such articles from being removed and can result in a tourniquet action. Do not use a tourniquet or ice, as they can increase tissue damage. Do not cut the skin or apply suction to the site of the bite. Clean the wound with water to remove residual venom on the skin and reduce the risk of infection.

General Biology, Reproduction,

and Behavior

Reproduction

Snakes typically mate in the spring. Female snakes may lay eggs, retain membrane-covered eggs inside the body during incubation, or give birth to live young. Eggs hatch and young are born in late June through early fall depending on latitude and species. Young copperheads and rattlesnakes are retained in the body of the female during incubation. They are born within a transparent egg sack during late summer or early fall. Juveniles of venomous species are just as venomous as adults.

Nesting/Denning Cover

Snakes do not nest. They seek locations for protection and thermoregulation. For example, a sun-exposed rock provides warmth on cool mornings, and a rock wall provides protection and cool temperatures during hot weather.

Underground dens or hibernacula protect snakes from freezing temperatures. Snakes use hibernacula in and around structures including sump pumps, rock walls, basements, crawl spaces, and other locations that are safe from winter freezing. A single winter hibernaculum may contain multiple species and hundreds of snakes.

Behavior

The behavior of snakes is determined more by temperature than by season. Snakes become lethargic at temperatures below 50°F. In most cases, snakes will move away when approached. When cornered, snakes react with a variety of defensive tactics that vary by species. Defensive tactics include playing dead on their back, hissing, opening the mouth in a menacing manner, coiling, emitting an odorous fluid from the vent, striking, and biting.

Habitat

Most species of snakes have specific habitat requirements. Some species live underground while others, such as green snakes, primarily live in trees. Generally, snakes live in cool, damp, dark areas where prey is available.

Areas around the home that are attractive to snakes include piles of firewood, old lumber piles, junk piles, flower beds with heavy mulch, gardens, basements, shrubbery growing against foundations, barn lofts (especially where feed attracts rodents), attics in houses where rodents or bats are present, banks of streams and ponds, lawns with long grass, and abandoned lots and fields where boards, tires, and planks are present to provide cover.

Food Habits

All snakes are predators, and different species eat a variety of sizes and kinds of animals. Rat snakes primarily eat rats, mice, chipmunks, bird eggs, and baby birds. King snakes eat other snakes, rodents, and young birds. Some snakes (e.g., green snakes), primarily eat insects. Northern red-bellied snakes and Eastern worm snakes eat earthworms, slugs, and salamanders. Water snakes primarily eat fish, frogs, and tadpoles.

Voice, Sounds, Tracks, and Signs

Some snakes, such as bull snakes, may hiss in such a manner that sounds like a rattlesnake. Hognose snakes will puff. Many snakes shake their tails, which can sound like a rattle.

Snakes rarely leave signs of their presence. It takes a careful eye to notice disturbances in soil that indicate the movement of snakes. Look in attics, crawl spaces, and outbuildings for paths in dust, drags through spider webs, as well as skins that have been shed. Shed skins tend to be 20% longer than the total length of the snake.

Damage Identification

Property owners typically discover the presence of snakes by direct observation or discovery of a skin. The fear of snakes is the most common conflict.

Damage to Landscapes

Snakes do not harm landscapes or gardens. They help reduce populations of insects and rodents, and usually are considered beneficial.

Damage to Crops and Livestock

Some snakes eat eggs and young birds. A classic sign of snake presence is the daily disappearance of eggs from nests. Most mammals break several eggs and leave the shells behind. Snakes swallow eggs whole, and usually just one per day. Pets or livestock may suffer serious injuries if bitten by a venomous snake, especially if the bite occurs on the nose or face.

Damage to Structures

Snakes do not damage structures.

Damage Prevention and Control Methods

Most methods for snake control are inexpensive, except for snake-proof fences. It is valuable to spend time educating people about the benefits of snakes.

Habitat Modification

Reduce food sources, including populations of rodents, fish, and invertebrates. Keep vegetation closely mowed. Remove bushes, shrubs, rocks, boards, firewood, and debris lying close to the ground. Alter sites that provide habitat and protected basking locations.

Exclusion

Seal all openings ¼ inch and larger with mortar, ⅛-inch hardware cloth, sheet metal, Copper Stuf-fit, or Xcluder™. A snake-proof fence, or boundary made from lava rocks may be effective for excluding snakes from an area.

Frightening Devices

Frightening devices are not applicable for snakes.

Repellents

Several snake repellents for have been promoted and are registered by EPA. However, none have undergone extensive research to demonstrate effectiveness for real-world applications.

Toxicants

No toxicants are registered for use on snakes.

Shooting

Use a shotgun or small-caliber rifle to kill snakes only when health and safety are at risk. Shooting may be limited by local firearm discharge regulations.

Trapping

Use funnel or pitfall traps with drift fences to capture snakes. Glue-board traps can be used to capture snakes. The snake can sometimes be released by smearing vegetable oil on the snake to deactivate the glue that is holding the snake. This does not always work, and capturing snakes on glue boards can be inhumane.

Other Methods

A heavy blow to the head or neck with a hoe or shovel will kill a snake.

Place piles of damp burlap bags or towels where snakes have been seen. Use a hook to check beneath the piles, and a snake tong to capture snakes that are present.

Disposition

Relocation

Relocation is appropriate when snakes are being rescued, or when exclusion likely will prevent their return.

Translocation

Translocation is not recommended, as snakes likely will lose access to their hibernaculum and habitat needed for survival. In addition, translocation increases the risk of disease transmission among populations of snakes. Translocation is illegal in many states without a permit. Consult a professional herpetologist for additional information on how to remove live snakes.

Euthanasia

Carbon dioxide is an effective method for euthanizing snakes. Cervical decapitation also is permitted. Use caution with venomous snakes as the venom remains potent following death.

Resources

Web Resources

Government or private agencies, universities, extension service.